Inside BENEO’s new pulse plant: pioneering sustainable protein from faba beans

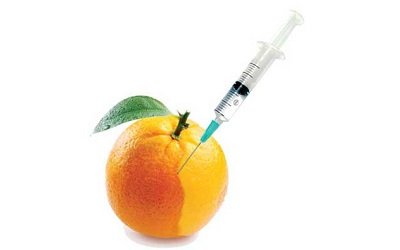

Himachal Pradesh High Court recently directed authorities to submit their opinion on the use of oxytocin vaccine in milk, fruits and vegetables. In Coimbatore half the ghee samples were substandard, did not mention ‘not fit for consumption’ and had labels printed in unreadable font. Even Vanaspati adulteration was rampant. HP or Coimbatore are no exceptions. The problem appears to be widespread. Food adulteration and unregulated use of pesticides and antibiotics in India seems to be worsening day by day.

One-fifth of the food items in the market, tested by government labs last year, were substandard or adulterated. Out of 72,000 samples analysed in 2013-14 over 13,500 were found to be adulterated, as per Public Health Ministry figures. But the problem is much more severe since as per Consumer Affairs Ministry data 87.3% of food product samples – almost four out of five – tested were adulterated. Milk seems to be one commodity that is facing adulteration on large scale. According to FSSAI survey of 2012, only 31% samples collected from 33 states conformed to FSSAI standards and the rest were adulterated with detergent, fat and urea as well as diluted with water.

It is a welcome move that the government has constituted a time-bound special task force to propose amendments to the FSS Act to make it more stringent. However, from earlier experiences it must be understood that merely amending the statute to make it stringent is not enough. What is needed in Indian context is steps for effective implementation of the law. Otherwise we are always known as the best law makers and the worst implementers.

A step by a district court in US may be a good pointer for India to consider and incorporate in the law. The court refused to dismiss a suit against the food safety audit firm (a lab) to make it answerable in a case of sale of contaminated food and the subsequent problem the consumer had to face. The lab, which was hired to audit the facilities and procedures to ensure that the manufacturing facility met applicable and cleanliness standards, gave it superior rating despite deficiencies just before a food-borne outbreak caused by contamination. The court held that the lab also owed a duty to consumers under general negligence principles.

Another important and fairly effective solution could be registration and licensing of every food business operator (FBO) as planned by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI). Of which the licensing part is much easier as it is for organisations from the organised sector. The real problem is registering every small roadside food hawker as FBO as their number is vast and they are part of unorganised sector.

Food contamination in itself is a serious issue. And its gravity enhances multifold when it is said, ‘Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.’ Contaminated food will not act even as pure food, leave apart as medicine. It is slow poison increasing risk of non-communicable diseases, other health hazards and at times even death. And it is needed to be treated with that severity and seriousness. This slow poison needs a strong antidote and fast cure.