Inside BENEO’s new pulse plant: pioneering sustainable protein from faba beans

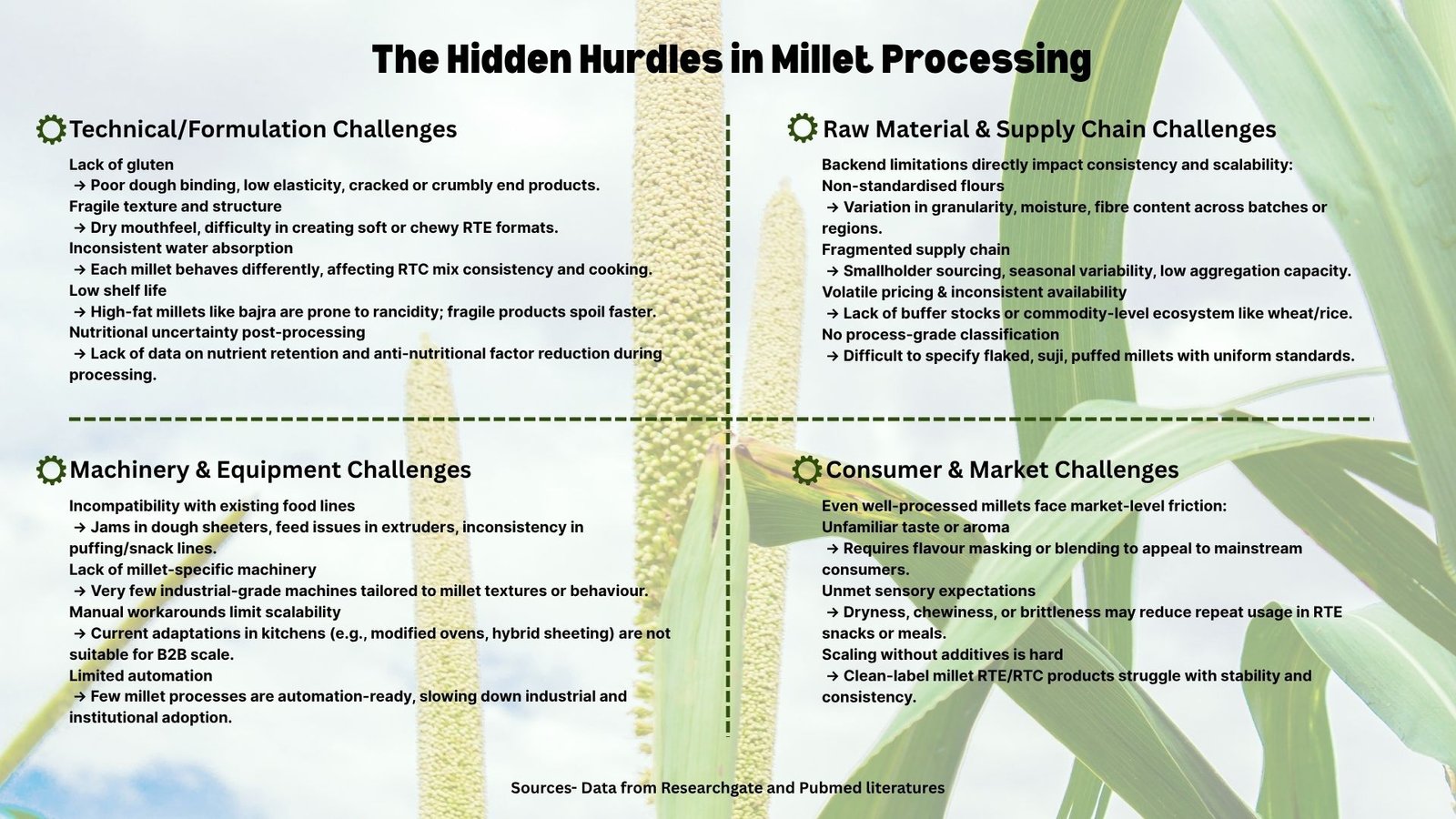

India’s millet moment has arrived — but beneath the surface of this nutritious grain’s resurgence lie critical operational roadblocks that innovators are quietly solving. From inconsistent flour textures and machine incompatibility to the lack of millet-specific equipment and fragmented supply chains, manufacturers and startups are pushing boundaries in formulation science, pre-processing, and tech adaptation. With India accounting for over 38.4 per cent of global millet production, and the value of the country’s millet-based packaged food product market projected to cross Rs 763 crore by 2030, the pressure is on to make millets work at scale. But turning this ancient grain into modern-ready mixes, baked goods, or extruded snacks isn’t as simple as swapping out wheat. It requires custom-engineered flour blends, new food machinery, and resilient sourcing strategies — the behind-the-scenes innovation that’s quietly powering the millet revolution.

Modern Makeover for Millet

Since the UN declared 2023 the International Year of Millets (IYoM), India has witnessed an unprecedented surge in interest, investment, and innovation around these ancient grains. Millets, once sidelined as coarse grains of rural kitchens, are now being celebrated as superfoods with immense health and climate resilience benefits. Government initiatives, startup accelerators, agri-tech innovations, and major FMCG players have all come together to give millets a modern makeover. The result? A wave of millet-based products is flooding the Indian market, ranging from breakfast cereals, cookies, and noodles to health bars, extruded snacks, and instant mixes.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, over 500 millet-based product Stock Keeping Units (SKUs) were launched in India within a year of the IYoM campaign. Retail shelves in urban India are now lined with millet-based offerings from both legacy brands and new-age startups. Brands like Britannia, ITC, Tata Soulfull, Slurrp Farm, and 24 Mantra have already launched millet variants in popular formats, signalling that millets have officially arrived in the mainstream.

One of the standout examples of this transition is Hyderabad-based startup Troo Good, which has scaled its millet chikki production to an astounding 2 million units per day. With a projected revenue of Rs 100 crore this year, the company operates on a farm-to-fork model, sourcing directly from over 15,000 farmers. Its innovative millet-based products are not just winning over retail customers, they’re also making their way into government nutrition schemes like the mid-day meal programme, thanks to state-level collaborations. This kind of integrated model exemplifies how Indian startups are helping reshape the narrative around millets, from niche to necessary.

India’s millet movement also gained global attention when the G20 Summit menu featured millet-based gourmet dishes like oxtail millet leaf crisps, barnyard millet pudding, and millet-scented Kerala red rice. This symbolic inclusion wasn’t just about promoting indigenous grains; it was a bold statement positioning millets as climate-friendly, gluten-free ingredients of the future, capable of holding their own on the world’s most prestigious dining tables.

But as India’s “millet moment” gains momentum, a complex reality is emerging beneath the surface. The real challenge is no longer just growing millets, it’s about transforming them. And that transformation is far from easy.

Unlike wheat or rice, millets are not naturally suited to industrial-scale processing. Their high fibre content, bran layers, and low-fat gluten-free structure make them technically difficult to handle in modern formulations. Product developers face multiple formulation hurdles, from poor dough binding and fragility during baking to unpredictable water absorption and machine incompatibility. Roti and khichdi may be easy to make with millets at home, but turning them into shelf-stable, ready-to-cook (RTC) or ready-to-eat (RTE) products at scale requires science, precision, and innovation. Moreover, the shift from traditional consumption to modern applications like baking, extrusion, blending, and dehydration demands a deeper understanding of millet behaviour, how each variety (like ragi, bajra, kodo, or foxtail) reacts during grinding, flaking, or puffing. And the absence of standardised flour specifications, functional benchmarks, and millet-specific processing lines further complicates the task for manufacturers and startups alike.

As India positions itself as the global leader in millet innovation, it must now focus not just on nutrition or awareness but on solving technical barriers that stand in the way of scaling millets. That means investing in customised flour blends, millet-friendly food processing equipment, and stable sourcing models that can deliver consistent quality for B2B, institutional, and retail applications. This story explores what it truly takes to make millets work beyond the label, from formulation science to tech gaps and supply chain fragmentation. Because beyond the buzz, making millets mainstream means mastering the science of transformation.

Why Millets Aren’t Plug-and-Play

As the Indian food industry rides the wave of millet resurgence, product developers are realising a hard truth: millets are not plug-and-play ingredients. Despite their remarkable nutritional profile, their structural and functional behaviour in food systems is vastly different from mainstream grains like wheat or rice. Turning them into commercially viable products requires navigating through a maze of formulation frictions.

For one, dough binding is a recurring challenge. Since millets lack gluten, the protein responsible for elasticity and cohesion in dough, formulations often fall apart, literally. Whether it’s rolling dough for millet rotis or producing cookie batter, the lack of gluten leads to fragility, cracking, and poor machinability. In baking, developers report dry textures and poor moisture retention, often resulting in short shelf life or crumbly products. These structural issues are amplified in industrial-scale production where consistency is key. Another complexity lies in water absorption rates, which vary significantly across millet varieties. Ragi (finger millet), for instance, absorbs far more water than wheat, while bajra (pearl millet) can become gummy when overhydrated. Uniformity in cooking becomes a challenge, especially for ready-to-cook (RTC) mixes and baking flours.

Satyajit Hange, Co-founder & Farmer at Two Brothers Organic Farms (TBOF), explains how his company addressed these limitations using specific pre-processing techniques, “Millets are inherently rich in fibre and nutrients, but their dense structure makes them difficult for direct use in everyday cooking. Techniques like puffing, flaking, and parboiling are crucial not just for improving digestibility and texture, but also for making cooking convenient. These methods make millets more accessible as substitutes for common grains in ready-to-cook and ready-to-eat formats. One of the key challenges we face is the lack of gluten, which affects dough elasticity and binding. Moisture retention is also tricky, often leading to crumbly end products. In terms of shelf life, high-fat millets like pearl millet can go rancid if not properly handled. At TBOF, we have developed custom solutions such as roasting, parboiling, and puffing, which have helped us overcome these hurdles while staying true to our commitment to clean, traditional, and nutrient-rich food systems.”

These tailored methods are not just industry practices; they are backed by science. A 2024 study published in Food Chemistry Advances found that controlled flaking and toasting can reduce phytic acid by up to 49 per cent, thereby boosting mineral bioavailability—iron by 35 per cent, zinc by 44 per cent, and calcium by 77 per cent. Such gains in nutritional value are crucial for millets to live up to their superfood label in modern formats. In pilot trials, fibre-controlled flour blends were shown to reduce dough breakage by nearly 30 per cent and improve softness retention in baked goods by over 40 per cent—game-changers for product developers aiming for quality consistency.

Meanwhile, Just Organik has made significant investments in millet-specific flouring infrastructure. According to Pankaj Agarwal, Co-founder and Managing Director, Just Organik even basic milling processes need to be redesigned for millets. He says, “Just Organik has been one of the early proponents of millets and operates a state-of-the-art millet processing facility and is the first ever company to export Organic millets to Denmark. Over the years, we’ve collaborated with diverse partners to cater to unique requirements across the value chain. Millets, though tiny, require highly specific processing techniques. Their high fibre content, while nutritionally beneficial, can present challenges for the RTE and RTC segments. At Just Organik, flouring millets goes far beyond basic grinding—it begins with meticulous grain preparation. We customise de-husking and polishing to adjust fibre content, colour, and texture, followed by carefully calibrated temperature, pressure, and sieving during secondary processing to achieve the desired output. These advanced capabilities make us a preferred supplier for millet-based flours, as well as RTE and RTC applications. Our deep understanding of processing, combined with a focus on sensorial and culinary performance, has enabled us to launch successful millet-based products. Among them, the Multi Millet Melange and Gluten-Free Dalia have emerged as customer favourites across age groups.”

This detailed approach, from grain conditioning to temperature-controlled milling, demonstrates the level of precision required to make millets industrially functional. It’s not just about grinding a grain; it’s about engineering a texture, a behaviour, and an end-user experience.

Wellbe Foods offers a third perspective by highlighting how source-level specifications and granulation control are vital in overcoming fragility and shelf-life concerns. Gaurav Manchanda, Founder and Director, Wellbe Foods, explains their integrated strategy, “Millets hold immense promise in the clean-label, health-forward food movement, but their use in ready-to-cook and ready-to-eat formats poses challenges like dough fragility, low water retention, and machinery incompatibility. At Wellbe Foods, we address these through precise specifications at the source for customised flour blends, precise granulation, and pre-processing techniques such as puffing, flaking, and suji-making, along with fibre-level adjustments that improve hydration, binding, and shelf life without additives. Our expanded millet range now includes Foxtail, Pearl, Barnyard, Proso, Browntop, Jowar, Ragi and Kodo in flours, flakes and rava formats. To support consumers unfamiliar with millet cooking, we also offer convenient, nutritious options such as millet noodles and dosa mixes across brands, making healthy eating both easy and exciting.”

Underlying these industrial efforts is a growing awareness that millets are anything but plug-and-play. To succeed, product developers need grain-level customisation, algorithmic moisture control, fibre calibration, and smart preprocessing, whether roasting, puffing, parboiling, or suji-making. These targeted interventions help align ancient nutrition with modern food systems, unlocking scalable, functional, and flavorful millet products for today’s consumers and foodservice channels.

Millets require more than nutrition claims; they require formulation engineering. Custom flour blends, optimised granularity, fibre control, and scientifically validated pre-processing are now foundational. Far from being a simple swap-in for wheat or rice, millets demand deep technical mastery, and those who succeed will set the standard for future-ready food innovation in India.

Reimagining Millet Processing

While millets hold promise as nutritious grain alternatives, the industrial machinery ecosystem is still catching up with their unique processing needs. Most existing food lines, from dough mixers and extruders to sheet formers, are engineered for wheat or rice. Millets, which lack gluten and behave differently under heat and pressure, routinely present challenges in product quality, efficiency, and consistency.

Dough handling, for example, becomes particularly problematic when working with millet blends in automated lines. Poor sheet formation, brittle dough, and frequent machine jams or underfilled items are common issues. Similarly, when creating high-moisture millet snack lines or extruded items, feed behaviour and product expansion change drastically compared to conventional grains. These operational gaps slow product development and increase costs.

At the CSIR–Central Food Technological Research Institute (CFTRI) in Mysuru, engineers have attempted to close this gap with millet-specific equipment innovations. In late 2023, at the IFCoN Expo, CFTRI showcased machinery such as ragi mudde makers, jowar roti machines, tiny millet mills, and a pedal-operated millet dehuller with up to 97 per cent husk separation efficiency and 90 per cent dehulling for groups like little millet, foxtail millet, and kodo millet. When it comes to private-sector innovation, startups and food-tech innovators are stepping in. Some are testing modified extruders and puff-snack plants capable of processing millet grains into crispy snacks at industrial rates of up to 500 kg/hour. Others are developing semi-automated millet roti-making machines, as documented in the ICAR–Indian Institute of Millets Research (IIMR) research paper, offering capacities of up to 100 rotis per hour, with manual, low-footprint operation, and affordability under Rs 25,000. This type of focused agritech is helping small-scale producers but is yet to scale for industrial B2B applications. Scaling millet-based formats for institutional kitchens or RTC/RTE production requires specialised machinery that can handle grain-specific textures. Here, current standard lines often fall short.

At Compass Group India, culinary innovation is stepping in to bridge the gap. “Millets behave very differently from popularly used grains. Their water absorption, texture and binding properties pose challenges to shaping, baking, and consistency across high-volume formats. Unlike wheat or rice, there is a noticeable lack of standardised equipment for millet-based batters, doughs, or flours, especially in RTC/RTE formats. Scaling across institutional kitchens demands automation-friendly solutions, which are currently limited, At Compass Group India, we have creatively adapted equipment and processes like soaking, grinding, etc., while modifying pressure settings in sheeters or using hybrid ovens to handle millet-based recipes like tacos or gluten-free brownies.” says Chef Arjyo Banerjee, Chief Culinary Officer, Compass Group India.

This adaptive DIY approach highlights the demand for purpose-built innovation—Food&Beverage operators need fully integrated millet processing lines to ensure nutritional retention, yield consistency, and operational efficiency. “There is a strong need for millet-specific processing lines to support consistency, nutrition retention, and volume efficiency. Purpose-built innovation in this space can be a game-changer for foodservice operators looking to champion millets at scale,” adds Banerjee.

Academic institutions are stepping forward to fill the void. At the National Institute of Food Technology Entrepreneurship and Management, Kundli (NIFTEM-K), innovations are geared toward industrial adoption. Emphasising the need for advanced processing lines for millet-based product development, Arun Om Lal, Industry Chair Professor, NIFTEM-K, highlights, “I strongly believe that innovation in food processing technology is crucial for promoting the use of millets. Currently, there is a significant absence or limitation of millet-specific food equipment, such as ragi roti machines, dough extruders, and flaking units, which hinders the efficient processing and adoption of millets. Most existing food processing machinery is built for grains like wheat or rice and often requires extensive modifications to handle the unique properties of millets effectively. This highlights an urgent need for innovating dedicated, millet-friendly processing lines. Additionally, automation gaps persist across factory settings as well as institutional kitchens in schools and hospitals, where consistent and efficient millet-based food preparation remains difficult. Addressing these gaps through technological advancements is crucial for enabling large-scale, standardised production.”

He further elaborates, “At NIFTEM-K, several R&D initiatives are underway to bridge the technological gap in millet processing and promote industry growth. These include SARTHI Technology, which integrates advanced digital technologies and sensors to enhance food processing efficiency; hybrid drying techniques and biodegradable film development to support sustainable packaging; and the creation of innovative ready-to-cook millet-based products, along with specialised equipment such as a state-of-the-art boondi-making machine. Through these projects, the institute aims to foster scalable, sustainable, and technology-driven solutions for the millet industry.”

The ICAR–IIMR, now the Global Centre of Excellence on Millets (Shree Anna), is another powerhouse fueling millet equipment development. “As demand for millet-based products grows, the availability of millet-specific machinery for primary processing and secondary processing like puffing, flaking and even roti making has traditionally been slow,” explains Dr Tara Satyavathi C, Director, ICAR-IIMR, while pointing out the lack of machinery specialised for millet products. “Thanks to our R&D efforts, many of these technologies and equipment are now available in the market. From millet analogue rice and gluten-free pasta to the recent development of sugar-free millet bread, our research continues to innovate for healthier, & scalable millet solutions. Processing lines compatible with millets are becoming accessible across scales, but operational know-how and standardisation remain a challenge,” she adds. Through IIMR’s Nutrihub and Common Facility Centre, over 85 millet-based technologies have been developed and licensed to startups and MSMEs. From millet analogue rice and gluten-free pasta to the recent development of sugar-free millet bread, IIMR’s research continues to innovate for healthier, & scalable millet solutions.

Despite this progress, most innovation remains piecemeal. The next step must be to integrate millet-compatible food lines—from dehulling to final packaging—with calibrated machinery that respects millet’s moisture dynamics, grain density, and dough behaviour. The lack of end-to-end solutions continues to constrain adoption in larger foodservice and packaged food settings.

Cracks in the Millet Supply Chain

As India pushes millets into the mainstream from government-backed PDS schemes to private-sector innovation in snacks and ready meals, the supply chain has become a critical pressure point. Beneath the celebratory headlines of “Shree Anna” lies a fragmented procurement reality: inconsistent textures, unpredictable pricing, and a near-absence of process-grade specifications. For food processors looking to scale up RTC, RTE, or B2B blends with millets, these cracks pose a daily operational challenge.

One of the core issues is the lack of standardisation across flours, suji, rawa, and puffed or flaked millet variants. Unlike wheat or rice, which benefit from decades of supply chain optimisation and clear process-grade definitions, millets remain largely informal in their post-harvest processing. Suji from finger millet may have a different granularity across states, and even within the same supplier’s batches, moisture levels or fibre content can vary, affecting product texture and shelf life.

“Processing millets poses several challenges, primarily due to the diversity in grain characteristics across millet types. Variations in size, shape, grain surface texture, hardness, and husk bonding complicate post-harvest handling. Even within the same small millet crop, factors like varietal differences, cultivation practices, and regional microclimates lead to inconsistencies in quality and behaviour during processing,” explains Dr Axay Bhuker, Scientist, Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar.

Dr Bhuker observes, “Adding to these hurdles is the relatively low shelf life of processed millets and their higher market price compared to conventional cereals. While rice and wheat benefit from scale, availability, and government support, millets face an uphill battle in securing affordability and consumer preference, particularly among low-income populations.”

Volatility is another critical issue. Most millet sourcing still depends on seasonal harvests from fragmented regions like Karnataka, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and parts of the Northeast. This means raw material prices are subject to climatic fluctuations, storage constraints, and inconsistent aggregation practices. Unlike industrial grain ecosystems that run on buffer stocks, most millet-based startups and SMEs face sharp cost swings between harvest and lean periods. Moreover, specific value-added formats like flaked or puffed millets are not widely available in standardised form, often made in local units with varying heat treatments and expansion quality.

Compounding these issues is the lack of consolidated scientific data around how different processing technologies impact the nutritional value of millets. As Dr B Dayakar Rao, Principal Scientist at ICAR–Indian Institute of Millets Research and CEO of Nutrihub, points out, “There is a significant lack of comprehensive data on how different processing technologies affect the nutritional characteristics of millets. We currently don’t have a clear framework that outlines the best processing methods to enhance nutrient availability and reduce anti-nutritional compounds. Additionally, the measurement of physiologically active compounds, such as polyphenols and flavonoids, in processed millet products compared to raw grains is still limited. There is also a pressing need for scientific research into the resistant starch content of millet-based foods and its therapeutic applications.”

This underscores that the supply chain challenges aren’t just logistical; they’re deeply linked to knowledge gaps that still exist in millet processing and nutrition science. Without consistent ingredient profiles and validated nutritional outcomes post-processing, it becomes difficult for companies to develop stable, scalable formulations for the mass market.

Need for Backend Revolution

The road to making millets truly mainstream goes far beyond front-end marketing or product launches. Their success in modern food systems hinges on what happens behind the scenes—in R&D labs, sourcing networks, and processing plants. Without backend innovation, millets risk being reduced to a short-lived trend rather than a permanent part of India’s food future.

To scale millet-based products, from cookies and noodles to ready mixes and batters, companies must invest in processing technologies and ingredient-level research. This is where flour engineering becomes a critical part of the backend. Food-tech firms and startups are now beginning to develop custom blends of millets with oats, barley, or legumes to optimise product texture, binding, and shelf stability. This approach not only enhances the sensory appeal of products but also improves their scalability and consumer acceptance.

For millets, specialised equipment such as ragi roti machines, millet-compatible extruders, or moisture-controlled puffing systems is needed to enable consistency at scale.

Sourcing is equally crucial. Millets today face serious inconsistencies in quality. Suji, rawa, and flour from the same millet variety can differ in granularity, moisture, and fibre content depending on the supplier, region, or batch. This unpredictability makes it hard for manufacturers to ensure product uniformity. Moreover, because of fragmented procurement systems, prices can fluctuate wildly, and there’s a lack of process-grade specification, unlike with wheat or rice, which have decades of standardisation.

To truly scale up millets, the entire backend needs a rethink—from farmer aggregation and dry chain logistics to standardised flour specs and equipment design. Companies that prioritise backend readiness—through investments in R&D, pre-processing, ingredient blending, and sourcing—will be the ones that lead India’s millet journey into the future. Stressing on this, Dr Pavuluri Srinivasa Rao, Professor, Agricultural and Food Engineering Department, IIT Kharagpur, comments, “There is a strong need for investment in efficient and user-friendly processing machinery tailored to millets. Automating these processing lines can not only enhance throughput but also bring down labour costs. At the same time, millet processing opens up significant opportunities for mass entrepreneurship and product value addition. We need to explore value-added technologies, diversify processing methods, and scale up machinery for commercial millet- based food production. However, more research is essential to strengthen these areas and truly mainstream millets.”

Millets may have the nutrition story, but without backend capability, they won’t sustain in competitive product categories like bakery, RTE, or foodservice. A millet cookie or ready mix must not only be healthy, but it must also work every time, taste consistent, and scale without failure. That kind of reliability only comes when innovation runs deep across the supply chain, not just at the surface.

Author – Mansi Jamsudkar Padvekar